Drone-based photogrammetric reconstruction, 6DOF interactive installation

In the interactive installation, Clouds of the ancient world, eight ancient sites are modelled in 3D photogrammetric point cloud, each of them keystones of early civilization and ancient culture, and all listed as UNESCO world heritage sites.

All texts are sourced from Iconem, unless otherwise cited.

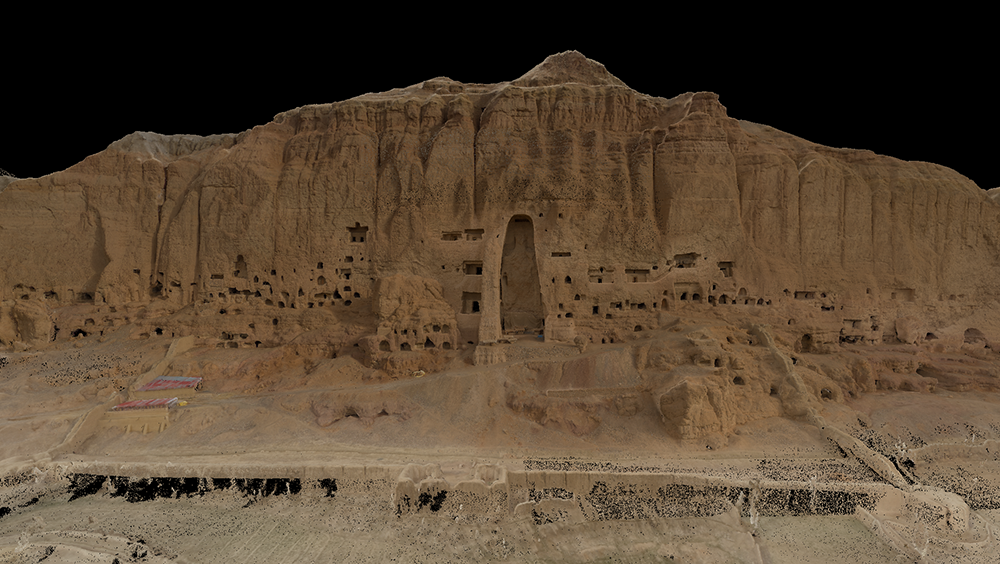

The Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan

The Bamiyan cliffs feature hundreds of caves both at ground level and all around the former location of the three giant Buddhas. Even if the great Buddhas were the main objects of veneration, also the system of chambers had a role in the religious life. This is a complex cave system, each with an average diameter of 8 to 10 metres. The four or five groupings that remain well preserved are directly connected to the two giant Buddhas, however they have been threatened by the rockfall from the cliff, which has already ruined the stairs that connecting them and many of the ancient aisles. The inhabitants of Bamiyan have made new stairs and passages in the rock to reconnect the caves. Iconem’s use of drones has enabled a photogrammetric survey to develop a 3D model, which provides a complete reconstruction of the site.

Aleppo and Palmyra, Syria

The city of Aleppo was first mentioned in cuneiform tablets unearthed in Ebla and Mesopotamia, that noted it for an impressive commercial and military proficiency. According to some historical sources, it may have been inhabited since the 6th millennium BC, which would make it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. Its strategic location, between the Mediterranean Sea and Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) made this place protagonist of a very long and intense history. The same site was once the agora of the Hellenistic period, later on the garden for the Cathedral of Saint Helena during the Christian era of Roman rule in Syria. The impressive citadel of Aleppo overlooking the city; the vast souk, one of the largest covered markets in the world; and the 12th-century Great Umayyad Mosque are especially culturally important, yet all sustained heavy damage. Aleppo was the second largest Syrian city before the Syrian Civil War started in 2012. Iconem worked with the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums of Syria in 2017, using drones to scan thousands of square metres to document these treasured sites.

Palmyra, in Syria, meaning the ‘Pearl of the Desert’, is a mythical Greco-Roman site that suffered violent destruction in 2015. When a monument has undergone a violent attack, the priority for its preservation is to gather the complete documentation that will serve as a basis for the archaeologists and architects who will work on the site. Following the destruction of the site by ISIS/Daesh in August 2015, Iconem was the first organisation to commence the digital documentation of Palmyra in partnership with the DGAM in April 2016, and again in April 2017; the two times ISIS/Daesh lost the control of the city.

The data collected by the teams of the General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums of Syria and Iconem, includes more than 50,000 photographs of the monuments of the ancient city, taken from the ground and with the help of drones. Among the many significant monuments of Palmyra reconstructed in Clouds of the ancient world, the ruins of temple of Bel were considered the best preserved of Palmyra before they were destroyed by militants of ISIL/Daesh in August 2015. Only the door of the temple has survived.

In contrast to the Temple of Bel, the Roman theatre of Palmyra, a building dating back to the Severan period, 2nd century BCE, has not been completely destroyed. In the 1950s the theatre was cleared from the sand and underwent extensive restoration works in the early 1990s. Before the Syrian conflicts, folk music performances for the annual Palmyra festival were hosted here. It was occupied by Daesh in May 2015 and recaptured by the government forces in March 2016 with the support of Russian airstrikes. At that time drone footage showed that the theatre still remained largely intact. When Daesh took control of Palmyra once again in December 2016, the facade of the theatre was demolished.

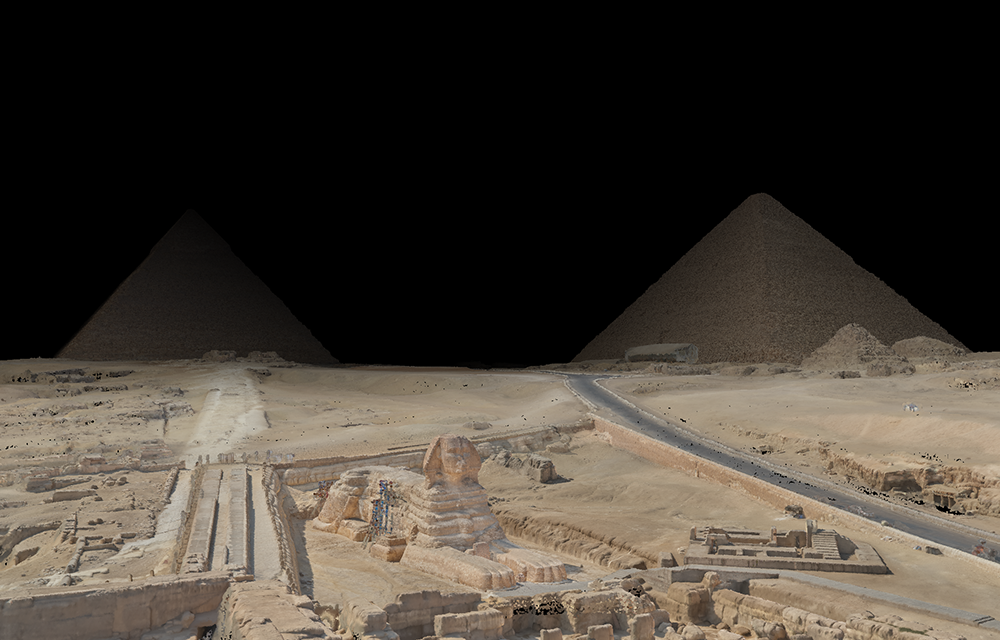

Giza, Egypt

According to Iconmen, the digital reconstruction of this site allows us to rediscover the Egyptian pyramids, for instance, ‘Right next to the pyramid of Cheops, on the Giza plateau, other architectural masterpieces defy the law of time; the Sphinx, the lion with a human head, and the pyramids of the pharaoh Khephren and Mikerinos. These monuments are the result of unequalled human and architectural prowess and are full of mysteries. With these two pyramids, the pharaohs continued their quest for perfection. Khephren rises to almost 143 metres and with its perfect right angles, it marks the apogee of this type of construction. Thanks to spatial archaeology, Egyptologists have also been able to penetrate its underground galleries to decipher the secrets of its construction. It is possible to see the Giza plateau as it was before the pyramid was built and to reconstruct for the first time the working-class city where the builders lived.

Placeholder

Meroe of Sudan

The ruins of the ancient capital Meroe are nestled between the Nile and Atbara rivers in Sudan. Towering Nubian-style pyramids dot the Island of Meroe, which was once the heart of the Kingdom of Kush. Meroe’s semi-desert landscape is drying up. Climate change is accelerating desertification. Sand batters the pyramids, eroding the intricate carvings and reliefs that cover the steep sides of the tombs. All traces of this once powerful empire will vanish unless action is taken to counteract the erosion. In 2017, in an attempt to record what remains of this site, Iconem used drones to scan the vast necropolis, in partnership with the Section française de la direction des antiquités du Soudan.

Placeholder

Leptis Magna, Libya

Leptis Magna is an extraordinary 3rd century CE Roman site in today’s Libya, which founded by the Phoenicians, and is also known as the Rome of Africa. Once one of the Roman Empire’s most impressive cities, Leptis Magna has been looted and neglected, and is now threatened by climate change. As it overlooks the Mediterranean Sea, the site and its harbour were ideally located for trade but its idyllic location now places it in danger from rising sea-levels. In spring 2018, Iconem digitised the ancient metropolis, including the Arch of Septimius Severus, in partnership with the Department Of Antiquities of Libya (DOA), the Mission archéologique française en Libye, and the Iconem Fund for Endangered Heritage.

Placeholder

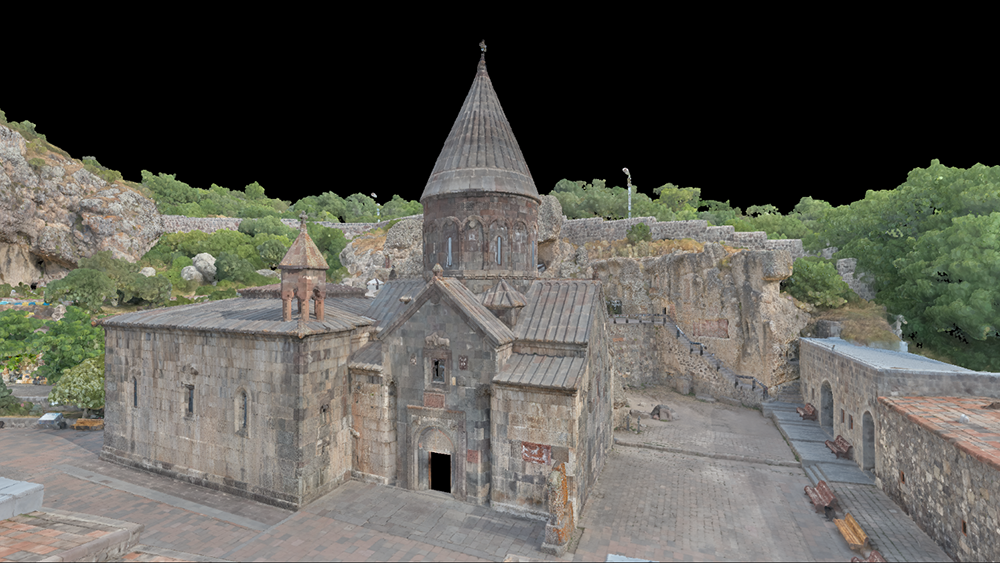

Geghard and Hagpat, Armenia

During a 2019 mission, led in collaboration with French artist Pascal Convert, Iconem travelled to Armenia to digitize various historical and religious sites, among them, the two monasteries of Haghpat and Geghard.

The monastic complex of Haghpat is located in the Armenia’s northern region of Lori Marz. A significant symbol of Armenian religious architecture, built between the 10th and 13th centuries, the function, location and stylistic characteristics of each new building were taken into consideration during their construction. As a result, a complex was built in harmony with the picturesque landscape, in a unique style developed from a blending of elements of Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture and the traditional vernacular architecture of the region.

The monastery of Geghard is a renowned ecclesiastical and cultural centre of medieval Armenia Surrounded by rock-cut churches and tombs, the monastery is a remarkable example of medieval Armenian religious architecture. Similar to Haghpat, the complex is set into a natural landscape, that of the Azat Valley. In addition to religious buildings, the complex is composed of a school, a scriptorium, library and residences for clergymen. The monastery was also renowned for its relics. Among them is the spear that wounded Christ on the Cross and which was allegedly brought there by the Apostle Thaddeus. It was kept in the Monastery for 500 years, and gave its name to the site: Geghardavank ‘the Monastery of the Spear’.